A recent operation by law enforcement authorities worldwide disrupted hundreds of sprawling botnets across the globe. The botnets, or networks of ‘bots’ that do the bidding of their masters, were powered by malware, most of which was classified by ESET researchers under the Win32/TrojanDownloader.Wauchos detection name, but also known as Gamarue or Andromeda by some other security vendors.

The international crackdown on November 29 came after a concerted effort by Microsoft and ESET researchers that ran for more than a year. ESET provided technical intelligence for the operation after tracking the botnets, identifying their command and control (C&C) servers, and keeping tabs on what those behind the threat were installing on victims’ systems. We sat down with ESET Senior Malware Researcher Jean-Ian Boutin to talk about ESET’s role in this operation, as well as about threats that botnets pose in general.

Given that Wauchos has been one of the longest-running malware families around, what made it so long-lived?

Wauchos has been around since 2011 and was available in underground forums and has thus been sold to various people. Also, its numerous features and continuing development were appealing to the cybercriminals who ended up using it for long periods.

Why did it take so long to crack down on it?

This type of operation takes a long time. As mentioned in the blog, this effort started in 2015. It took a long time to get everything ready for a law enforcement operation. Also, there must be appropriate entities that are willing to put the necessary resources into putting an end to a botnet. Thus, the botnet must be very prevalent and cause a lot of harm to instigate an operation on this scale.

Which countries bore the brunt of the infestation?

Most of the infestations we’ve seen in the past six months were in South-East Asia and South America.

What kind of devices were affected the most? Home computers, corporate computers, servers…?

Wauchos infection vectors included social media, removable media, spam and drive-by downloads. As none of these are targeting any particular group of users, pretty much every computer user clicking a link is a potential victim.

What was your role in the takedown operation, and what did your research and collaboration with Microsoft and law enforcement involve?

Our role in the operation was on the technical side: malware analysis and finding C&C servers used by the different Wauchos botnets. As this threat was sold in underground forums, it was important to make sure that all Wauchos C&C servers were identified and taken down simultaneously. We helped with this effort through our botnet tracker system.

How did you capture and analyze the malware behind the botnet?

The first step was to analyze the bot’s network protocol and behavior in order to include it in our botnet tracker platform. This platform can automatically analyze samples received from our clients, extract the relevant information and use this to connect directly to the malware C&C server. Through this, we can gather the relevant information for this operation automatically by analyzing the Wauchos samples reported to us by our clients.

How did you make sure the criminals were unaware of your research?

Of course, when working on this type of operation, it is of primary importance to make sure that criminals are not aware of it. So, we tried to inform only the people who needed to know about it and to keep the sensitive information private.

What was the most common type of damage caused by Wauchos after a computer was infested?

Historically, Wauchos was used to steal login credentials through its form grabber plugin and install additional malware onto the infected system.

What was the most common way in which the machines were compromised?

As Wauchos was bought and then distributed by a variety of cybercriminals, the infection vectors used to disseminate this threat varied greatly. Historically, Wauchos samples were distributed through social media, instant messaging, removable media, spam, and exploit kits.

Were there any signs obvious to the user that indicated that a computer had been compromised by Wauchos?

Not really.

How was the botnet monetized? I take it that money was the reason why the botnets were started in the first place.

As Wauchos was sold on underground forums, there were various monetization schemes. One of them was to use the form grabber plugin to steal passwords for online accounts. Another one was, for a fee, to install additional malware on the compromised machine, a wildly popular scheme amongst cybercriminals and known as ‘pay-per-install’.

What kind of C&C infrastructure did the Wauchos operators use to control the ‘zombie’ computers?

They were using several C&C servers located in various locations. It is these servers that were targeted in the takedown operation.

Was there any reliable way to detect that a bot was communicating with its C&C server?

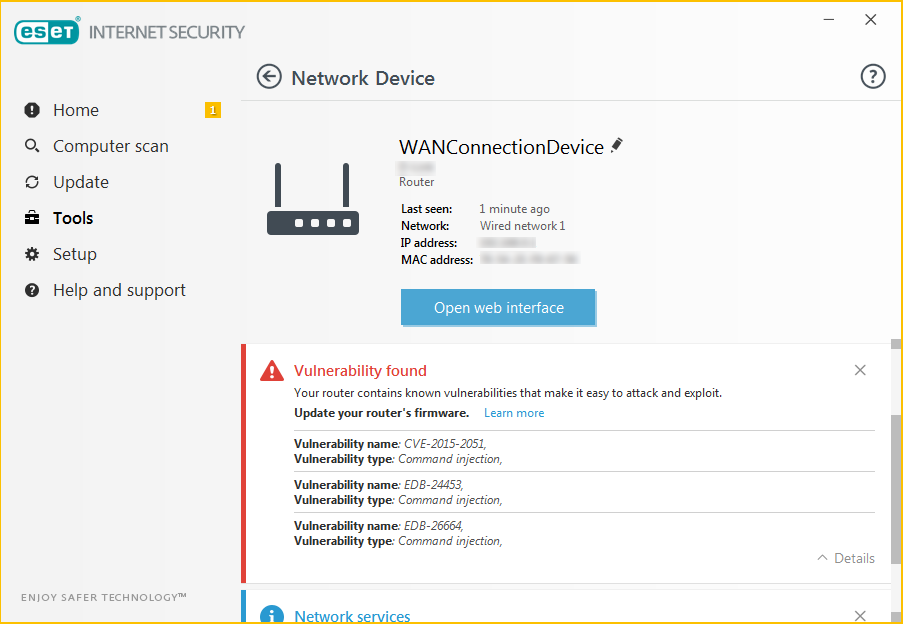

Wauchos bots were using a recognizable network pattern when communicating with their C&C servers. This allowed us to protect our users better by adding another layer of protection: the creation of network detections to be able to recognize when a bot was trying to reach out to its C&C server.

How did you find out about communication between an infested computer and its C&C server and how did that communication take place?

The details of the network communication can be found in the blog. It was obtained by reverse engineering the various samples.

Was C&C traffic encrypted?

Yes, it was using an RC4 key embedded in the binary.

How did the malware behind the botnet interfere with the operating system’s functionality?

Wauchos was interfering with the operating system in many ways. Among other things, it was attempting to disable Windows Firewall, Windows Update and User Account Control functions.

Did Wauchos use any anti-VM or anti-sandbox techniques?

As this malware family was for sale in underground forums, different cybercriminals were using different techniques, but yes, we saw samples employing anti-VM and anti-sandbox techniques.

Is there any way to determine how successful the rootkit plugin was in concealing the infestation?

Not really.

Based on your experience with botnet disruptions, what do you think lies in store for Wauchos now that it’s been obstructed?

It will probably slowly disappear as remediation is under way. For this type of long-lived botnet, it is very hard to clean all the systems that have been compromised by Wauchos, but as long as the good guys are in control of the C&C servers, at least no new harm can be done to those compromised PCs.

Generally speaking, what symptoms might alert everyday users that their computers have been ensnared into a botnet?

Depending on the malware family, it can be difficult to recognize that your computer is compromised. If you notice weird behavior from your computer such as – but not limited to – your security solution being disabled or no longer able to update itself, or if you realize that you are not receiving the normal Windows updates, malware might be the culprit. Using free tools such as ESET’s Online Scanner to scan your system can help to find and remove malware that might be causing these issues.

How can one make sure one’s computer doesn’t end up being part of a botnet?

Most of the common malware families are using old tricks and cannot install themselves without some help from incautious users. The usual recommendations of not clicking on random links or not opening attachments coming from untrusted sources go a long way towards staying safe on the internet.

Did you have a glass of champagne to celebrate the successful operation?

I did!

Source: Welivesecurity

Share Article